Measuring pressing in soccer

February 12, 2026 · 8 min read

Pressing. If you ever played soccer at any level, it was probably your least favorite part of the game (or at least it was for me, I'm sure the cross country kids loved it). Who wants to waste energy running at the opposing team when you could save it for your next encara-messi dribble through the entire team? Professional coaches do, that's who. And Raphinha. Literally no other player I know enjoys pressing (don't let Thierry Henry* fool you).

A quick description of pressing

For those of you who don't know, pressing (at least as I'll refer to it throughout the rest of this article) is the act of closing the space between you and the player on the ball, with the end goal of stealing it from them (or more likely forcing them into a situation where the only thing they can do is boot the ball and pray). Basically, it's an attempt to disrupt a team's build up play.

But coaches are onto something here. Pressing is incredibly important in the modern game, as more and more teams attempt to play out of the back. If you can press well, you prevent the other team from progressing the ball using quick passes, instead forcing them to boot the ball up the field and try to win duels against your hopefully big and tall centerbacks. Or, even better, you straight up just win the ball high up the field and turn defense into attack. You don't need to be Pep Guardiola to realize that winning the ball up the field = good for your chances of scoring.

The problem with current stats

While there exist a plethora of statistics for attacking (again that’s the fun part of the game), some of which are actually good, hardly any exist for defending beyond rudimentary stats like tackles, blocks, or interceptions. All of these are horrible measures of actual defensive contribution because they focus on outcomes not processes. Knowing a player intercepted the ball tells me nothing about their contribution. Did the offensive player make a terrible pass? Did the intended target not step to receive the ball? Etc. etc. As, Bill Walsh said:

What I want to measure is whether a player pressed correctly, i.e. where they taking the right process?

What makes a good press?

I talked with some college coaches, players, and used common sense to come up with this list. I know it's short, but as Johan Cruyff so elegantly said, "Football is a simple game".

Two things basically:

- Did you close down the ball carrier?

- Did you cut off immediate passing lanes?

The stats I mentioned above fail to capture any of this (there might be some correlation between closing down and blocks, but it’s probably not very high).

My Metric

My metric is built almost entirely from tracking data.

There are two parts to my metric. First I identify a pressing sequence, then I assign value to the presser. I define pressing sequences as situations when:

- A player receives the ball with no defender within 10 meters

- By the time they make their next action, a defender is within 5 meters

- At least 1 second passes in between these two events (basically a proxy for making sure the defender actually did some pressing)

To identify the pressing value, I combined the two things mentioned above that made a press valuable.

First, closing down the space. This is pretty easily measured by comparing the presser's velocity vector and the pressee’s (that’s not the word but whatever) position. Just using distance is not ideal because the orientation of the players matters. You want to press facing the attacker, not coming at them from behind. This is because you generally play the way you are facing (humans are not owls), so having someone behind you, while still annoying when trying to complete a pass, is much less annoying then having someone in front of you.

Second, I measure how well the presser cuts off passing options. Basically this comes down to comparing the passing options the player being pressed had before the press started, to the options they had once the press ended.

Measuring passing options is an interesting problem within itself, and I’ll write a separate blog about it in the near future, but for the sake of this article we can just pretend we have a somewhat accurate model of it.

Some fun examples

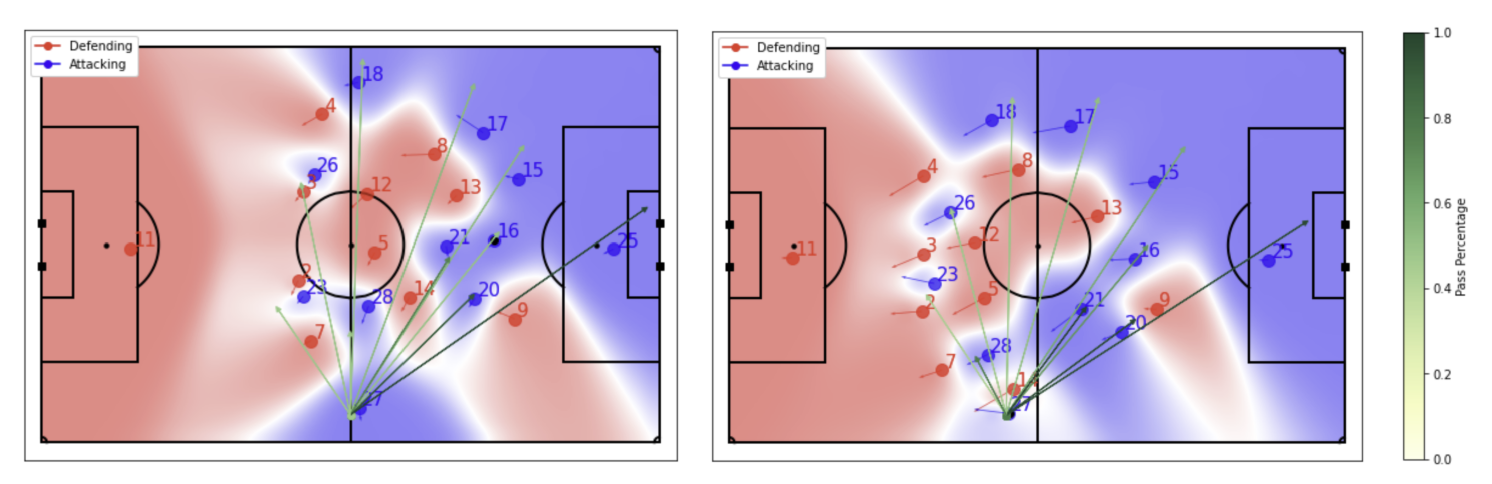

That was a lot of words. Let’s get some pictures to hopefully make it a little clearer. I apologize for all the passing lines I realize they clutter things a bit.

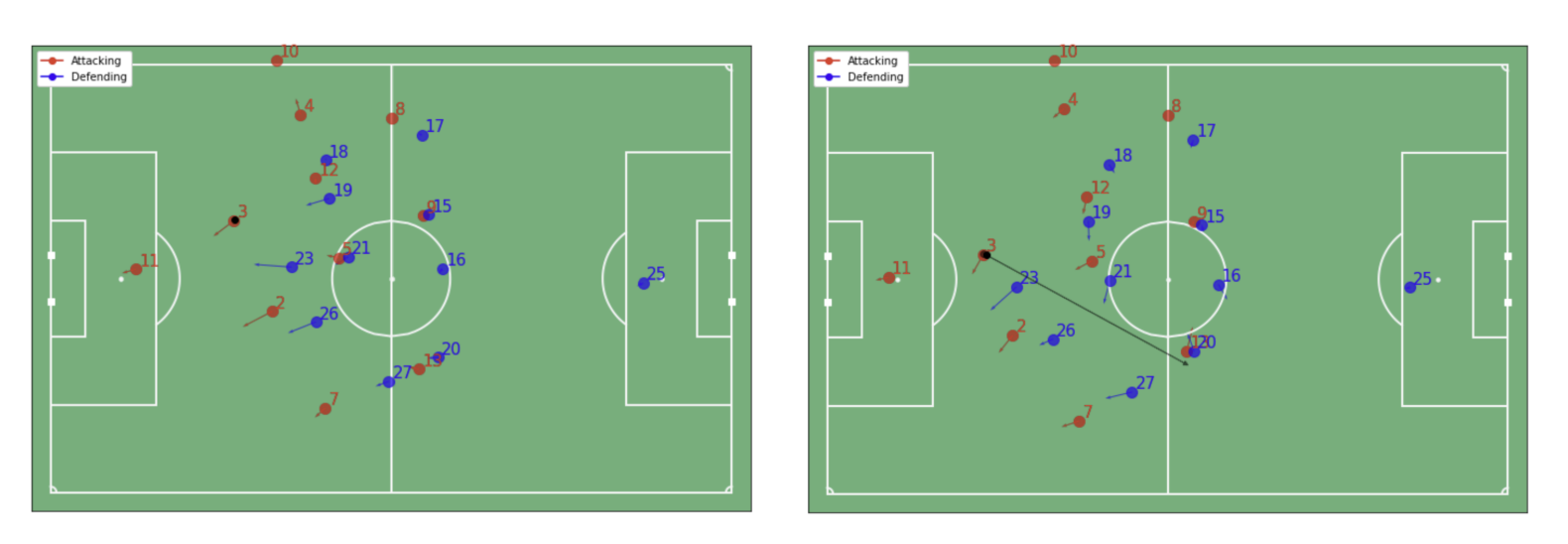

First, an example of a good press (Blue 27 has the ball). In the left image (the start of the press), there's a pretty open passing lane to Blue 28. In the right frame, the defender has curved their run and shut it down, making this a good press.

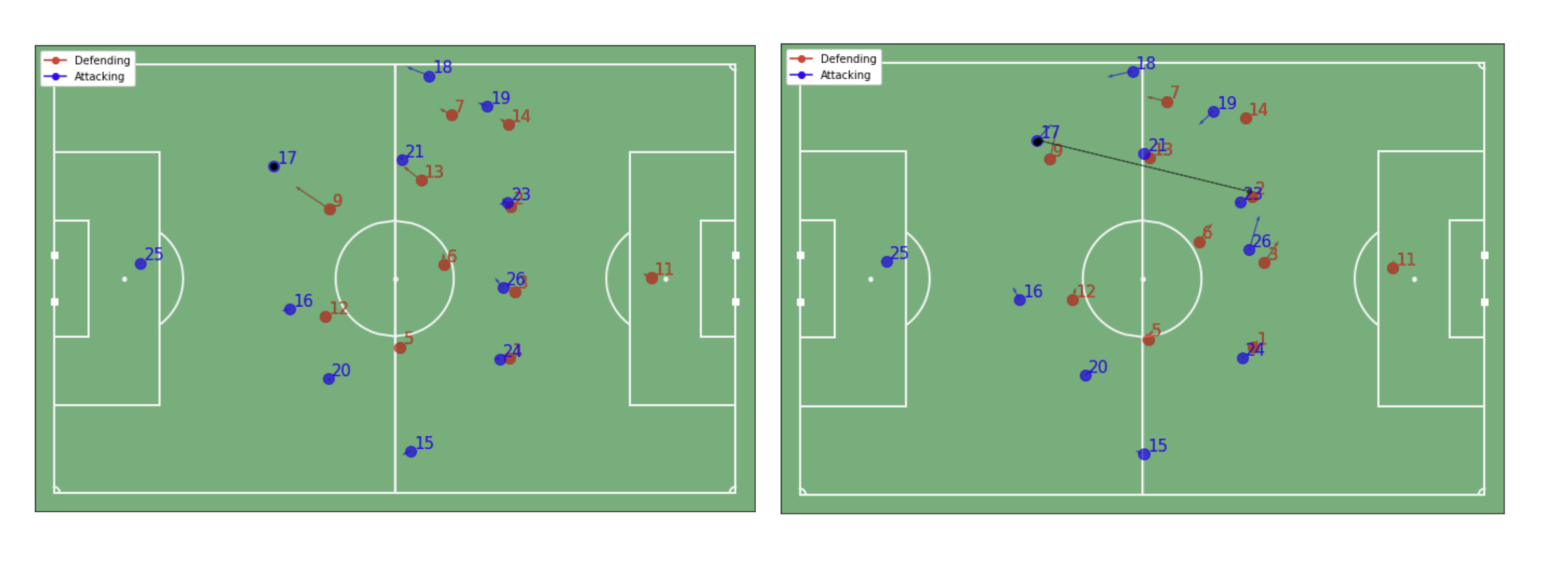

And now an example of a bad one. Blue 19 does a bad job of cutting off the forward passing lane to Red 8 since they kind of just run in a straight line. Instead they should have curved their run to force Red 4 to go back inside, where the Blue team was well situated.

Why the metric is useful

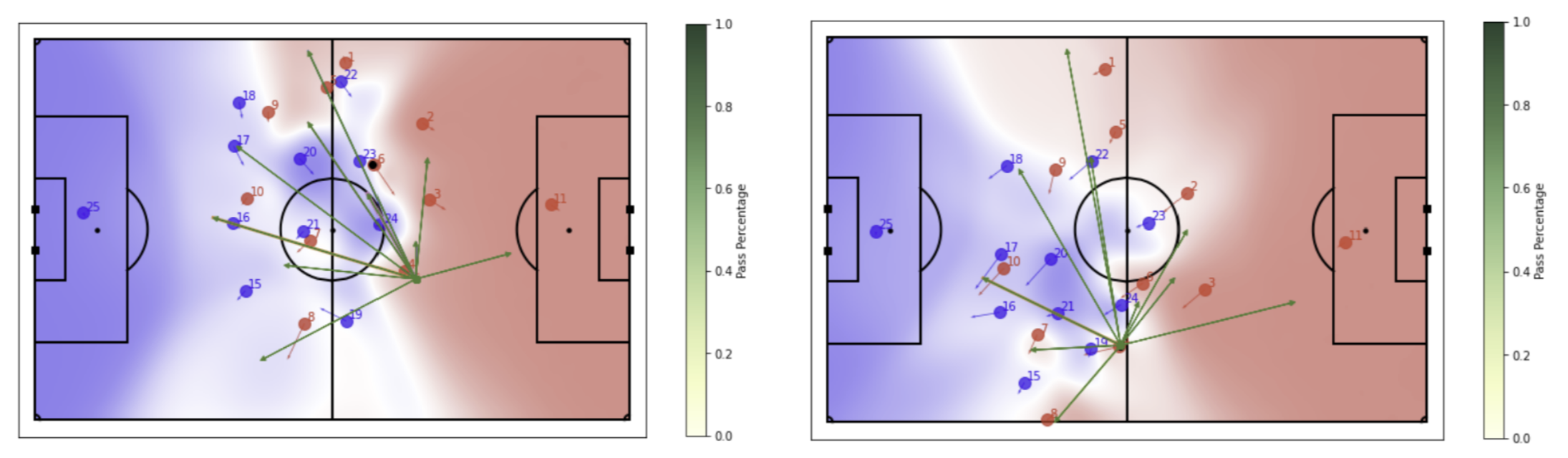

Going back to the terrible existing metrics I talked about. Take a look at this press, which ranked in the 7th percentile of my dataset.

The defender does a poor job on both parts of what constitutes a successful press. He doesn’t close the ball down (look at his velocity vector), and doesn’t cut off any passing lanes. However, the defender makes a terrible decision and attempts an absolutely audacious ball that predictably gets intercepted. As you can see, the outcome of an interception has little to do with a good press.

Now, the opposite. A press that ranked in the 90th percentile of my dataset.

Red 9 does a great job curving their run to prevent the easy pass back to Blue 16, and does a fantastic job closing down the space. This forces Blue 17 into a tough situation and a bad pass that gets intercepted by Red 2. Again showing how the interception stat (which Red 2 would have received credit for) is a silly way to measure who was playing good defense.

Support for my metric

My metric correlates negatively with things you'd expect: possession length, how far up the field the opponent gets their next pass, and the highest point the possession reaches. In other words, better pressing (as measured by my metric) leads to worse outcomes for the attacking team. This is a generally good sanity check that it’s capturing something of value.

This metric is just a start, but I do believe it captures something that no existing metric does: did the defender actually do their job, regardless of what happened next?

Caveats

This is not a perfect metric by any stretch of the imagination.

One obvious issue is that it fails to measure anything about the offensive player, assigning all value of the pressing to the defensive player. But sometimes players being pressed just do stupid things - giving the defender credit for this is a little silly.

Another nit I have is that this just considers cases where the player being pressed makes a pass, not taking into the account that he may just dribble around the defender (which would be very bad pressing indeed).

Also, as Michael Edwards would remind me, the metric doesn’t really take game state/context into account. For instance, late in the game, a team that is winning might invite pressure just to boot the ball up the field (or maybe, if they're Mikel Arteta’s Arsenal - that was their game plan all along!). These variables are hard to pull out of all the noise though, and I think over long horizons (one season or more of data roughly) it shouldn’t matter, since each presser should in theory be facing a similar distribution of game state + opponent strategies.

Next Steps

Some fun next steps (off the top of my head, I'm sure there's plenty more to go off of) might be:

- Calculating a metric adjusted for offensive player decision making/skill

- Calculating team based pressing metrics (i.e. measure how well a team constricts passing options, not just individual players)

- Compare players in the same system, since pressing in a team that parks the bus v.s. a team that gegenpresses is very different

*I am sorry for posting a tiktok this was just the first link on google and I'm lazy

**I don't have a lot of data so I'd take this with a grain of salt, but I believe in my metric and if data wasn't so expensive I'd test it on more and get some statistically significant results back